LAKE WATEREE – Multiple daring escapes, a hunger strike, illegal employment and black-market deals, a trip halfway around the world, and then a whole lot of hard work that began with exhausting menial labor but ended with an American dream come true.

It might sound like a movie, but it’s the real-life story of Tibi Czentye, who runs a business in Rock Hill and lives an otherwise quiet life on Lake Wateree, where his grandchildren come to visit.

“I really think it’s a blessing to live here,” said Czentye who sought asylum after fleeing communist Romania three decades ago and has since built a life in America. “If you work hard, you can accomplish the American Dream. It doesn’t matter if you are born here or you are born from other places,” he said, his thick Romanian accent at times blurring his English.

Czentye’s American Dream story began in the Romanian city of Timisoara around 1989. He was 30 years old. Romanian socialist leader, Nicolae Ceaușescu had imposed an austerity program on Romanians to facilitate the repayment of billions of dollars of debt Ceaușescu had amassed with such projects as building monuments to himself while the Romanian people did without. The oppression was growing more severe, and Czentye found his ambitions frustrated.

It was in Timisoara that the revolution began that eventually ended the brutal communist/socialist regime. But the revolution didn’t come soon enough for Czentye, a young engineer, whose skill and education were not enough to give him a voice in a system that was fundamentally at odds with his work ethic and the life he wanted for his family.

And besides that, he said, living conditions had long been unbearable under Ceaușescu’s brutal regime. Groceries were purchased only with very limited government ration coupons and required a day of standing in line each week. When his young son was ill in the hospital, he had to risk imprisonment – and turn over his savings – to pay bribes and purchase black-market medicine.

Anyone who complained about the system, he said, simply disappeared; the government took them, and they were never heard from again.

It hadn’t always been this way in Romania, he said; it began with promises of free things, which were enthusiastically received. But once the government realized it couldn’t keep its promises, the result was dictatorship and closed borders that made everyone a prisoner in their own country, with barely the means to survive, Czentye recalled.

That, he says, was the reality of socialism behind the Iron Curtain.

“People who today speak about socialism as if it were a good thing – or mistakenly praise the generous welfare states of capitalist Scandinavian countries as “socialism” – don’t understand the reality of suffering that this flawed ideology brought to millions of people in the 20h century” Czentye said.

Real socialism, he says, is merely a stepping stone to misery.

Under a system that, at best, provided the same bare survival to everyone regardless of their contribution, Czentye said he felt like he had three options: work like crazy, but not be paid for it; sit back and be lazy, and accept a meagre living; or risk his life to move to a free society that would value his work ethic and drive – and enable him to provide the life he wanted for his family.

So, he made a decision. He had to escape, or die trying.

He said he felt his best chance of success was to cross the border on his own and then apply through diplomatic channels to have his family join him. But when it came down to it, leaving them to make his escape was the toughest moment of his life.

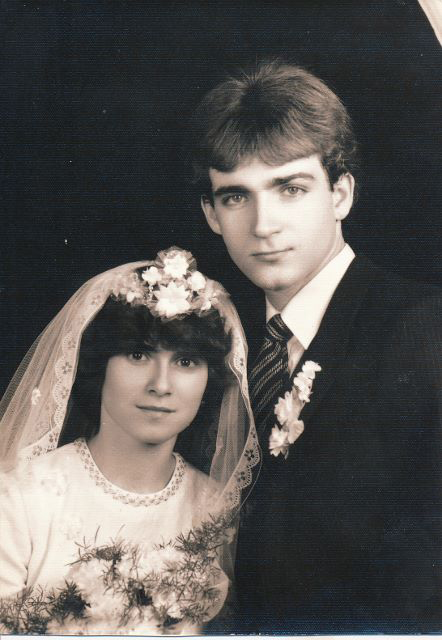

“I kissed my kids goodbye, and my wife,” he says. “It was very emotional because I had no idea if I was going to see them again or not.”

It took him two days and two nights to stay hidden while walking the 40 or so miles from his home in Timisoara to the border with Yugoslavia – a border with fences and towers and armed guards. For the last mile, he crawled to avoid being seen, twice having to freeze to avoid detection when spotlights came his way.

He made it across the border, but he wasn’t free yet. In Yugoslavia he was caught and jailed, and he had to escape again – which he did after three months of hard labor. The next country he snuck into was Austria, then West Germany. Ultimately, he wound up in the Netherlands.

There, he was kept in a camp for refugees where he languished for months before a hunger strike finally won him the opportunity to live in an apartment. With the identification card he received then, he petitioned for his family to visit from Romania.

Thanks to the subsequent overthrow of the Romanian government after Czentye’s escape from his homeland, the petition was granted.

“Because the regime in Romania was at that time trying to prove its legitimacy to the world, they allowed my family to leave. Of course, the ‘visit’ was permanent,” he said.

Czentye said he was not allowed to work in the Netherlands, but he did anyway – in jobs like landscaping and shipbuilding. For a while he commuted more than an hour and a half each way to Amsterdam to unload mountains of icy fish. The exhausting work pushed his body to the limit – but, he said, it was good money.

In 1991 he and his family were finally granted political asylum in the United States, and in July of that year they arrived in Portland, Maine. Government help was available there, but Czentye said he turned it down. His dream was to make it on his own, to seek his fortune in California. So he bought his family tickets on a Greyhound bus.

“I arrived in San Francisco with two luggages, two kids, my wife and God. This is how we start the life. And [for] five years I worked three jobs: in the morning in assembling, in the afternoon and the evening in a restaurant… and on the weekends, Saturday and Sunday, I used to work as a security officer in the banks.”

The assembly job was in manufacturing floppy disk drive duplicators – and his first business venture once he’d saved up some money was to buy a large inventory of the equipment to sell.

Then, with his knowledge of the industry and his engineering background, he developed a new product: disk duplicators for CDs and DVDs. He and his wife opened a business. They manufactured them, sold them and handled tech support.

In 1998, the whole family became citizens. The Czentyes’ sons were top students in their high school classes. Czentye and his wife worked hard and sent their two sons to college. Wanting to escape the high taxes and over-regulation of business in California, 11 years ago they moved to South Carolina. On this cross-country trip, they had a little more than two suitcases. It took several trucks to move their possessions and business here.

The business has since evolved with the times. They moved to blu-ray disc equipment and, more recently, secure data storage.

“We now have 10 employees. Our sons are married to nice Southern girls and have kids of their own,” Czentye said. In his spare time he enjoys hunting and fishing.

“I fought and I risked everything to accomplish this goal,” he says of the life his family has built here. “It’s a good feeling for me [to] build everything by myself… and to know the sky’s the limit.”

While it wasn’t long after he left communist Romania that it – and much of the communist world – collapsed under its own weight. It left behind many cautionary tales, Czentye said, not least of which is that the easy life promised by socialism never turns out to be what was promised – and freedom, while it may require more effort, ultimately offers a better path.

Czentye was able to accomplish the American Dream after arriving in America when he was almost 32 with his family and little more than the clothes they wore.

“This means anyone can – and Americans, especially young people, should ask themselves why they can take things like food and water for granted while people in many parts of the world cannot,” Czentye said.

The answer, he said, is freedom – which doesn’t guarantee a perfect outcome, but then no system does – but it does offer the opportunity to build one’s dreams.

“Nothing is free, that is sure, and America is not perfect but is the best country in the world,” he said. “We don’t have to change things that make us to be different from the other countries. We have to push and try to do even better.”